Apr 12, 2019

When humans try to recall images from memory, they involuntarily move their eyes in a pattern that is similar to when they are actually looking at the image.

James Hays, an associate professor in the School of Interactive Computing and the Machine Learning Center at Georgia Tech, and researchers from TU Berlin and Universität Regensburg, are looking at how these patterns, known as gaze patterns, can be used to retrieve images from memory so that it’s easier to find that same image – like an adorable dog photo – stashed away in the digital cloud.

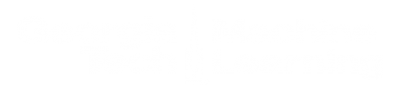

Through a controlled lab experiment and a real-world scenario, Hays and his co-authors have developed a matching technique using machine learning to help computers understand what image someone is thinking of, and accurately retrieve it from a computer folder – based solely on eye movements.

Using eye-tracking software in the lab, the researchers recorded the eye movements of 30 participants as they looked at 100 different indoor and outdoor images, ranging from picturesque lighthouse scenes to cozy living rooms. Participants were then asked to look at a blank screen and recall any of the 100 images they just saw.

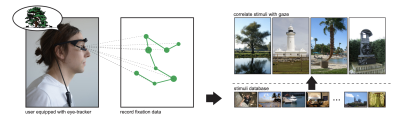

The researchers also conducted a realistic scenario by putting together a mock museum with 20 posters of various sizes and orientations spread throughout the “museum.” They outfitted each participant with a headset complete with a Pupil mobile eye tracker, complete with two eye cameras, and one front-facing camera. Participants were asked to walk around the museum and look at all of the images, taking however long they liked, and in whatever order they preferred. They took anywhere from a few seconds to over a minute looking at each poster.

After looking at all of the images, participants were asked to look at a blank whiteboard and recall as many of their favorite images as possible, in any order. Participants remembered between 5 and 10 of the total 20 poster images.

The results from both experiments indicated that the gaze patterns of people looking at a photograph contain a unique signature that computers can use to accurately determine the corresponding photo.

Using the data collected from the experiments, researchers created spatial histograms, or heat maps, that could be analyzed by their new machine learning technique to determine which photo someone was thinking about. Hays and Co. also used a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to look at the 2,700 collected heat maps.

“The ability to retrieve images using eye movements would be beneficial to those who are disabled or unable to search for images using their hands or voice,” said Hays. “Also, wearable technology is a huge industry right now, and we believe that tracking motion with the eyes would be a natural by-product of that boom.”

In Hays’ previous research, SketchyGAN, people are able to draw (rather than type) what they are looking for to get image search results. But, if images are mislabeled or people can’t draw that well, search results are not useful. Other attempts at image retrieval have included various types of brain scans, but those are often too expensive and impractical for everyday use.

While this new research may prove helpful to people, it does not come without limitations, researchers note. The scalability of the model in part depends on image content and how many images are in the database. The more images the database holds, the more likely it is that several different photos will produce extremely similar gaze patterns.

One proposed workaround to this potential issue is asking people to make more extensive eye movements than they normally would. At the moment, participants are not asked to do anything more intentional or out of the norm when looking at the images. Researchers think that by putting a small amount of effort back on the user, this would help the computer find the correct image.

Another foreseen problem is working with people’s memories. As people’s memories grow weaker with time or age, it will be harder to get a crisp gaze pattern and accurately return the right image. The team plans to explore these potential issues in the future by looking into the influence on memory decay and how it affects image retrieval from long-term memory.

The authors are also looking into combining gaze tracking with a speech interface, as that could be a rich resource for information. No matter which direction they go, the team believes that eye-movement image retrieval is not only possible but also a significant next step to improving human and computer interaction.

One might even say that before long, people will be able to find that favorite dog photo in the blink of an eye.

Further details on this approach to image retrieval can be found in the paper, “The Mental Image Revealed by Gaze Tracking,” which has been accepted at the ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI 2019), May 4-9.